By Amber B. Courtney

NABJ Monitor

The Black words “zaddy,” “finna” and “chile” have been added to Dictionary.com. It’s true. You can look it up.

These words, common to Black language, already had made their way into the vocabulary of White people within the last few years on social media, and now have been officially recognized by the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, which publishes Dictionary.com.

These words have been a part of Black linguistics for decades and were popular among African-Americans way before non-Black people knew the words existed.

John Kelly, the managing editor of Dictionary.com, says the site was simply doing its job.

“It’s our job as a dictionary to document and describe the English language as it is constantly changing,” he said.

Dictionary.com does not strive to act as gatekeepers of what is English and what it isn’t, he said, but to simply document words as they are used, no matter where they stem from.

“We have to do our best to keep up with language as it changes,” Kelly said, “and that includes taking inputs from different places, monitoring slang, including new definitions, and updating old definitions.”

Dictionary.com’s history with Black language has not always been so inclusive. In 2020, the entry for “black” included the synonyms “dark,” “dusty,” “sinful” and “devilish.” A controversy followed because one of the definitions of the word described people of color.

Random House then introduced “Black” with a capital B as a separate description of a person’s race, leaving “black” with a lowercase b with the controversial synonyms.

Kelly said the online dictionary includes more than definitions. It also includes etymology, where the word came from.

“We want to document language and that includes giving credit where credit is due,” he said. “So many words originate in the Black community but are miscredited to white teens on Tik Tok. If we are going to accurately describe the English language, giving credit to its origins is part of it.”

Even though many agree that Black language should be acknowledged by the dictionary, attempts to recognize Ebonics, or the entire system of African-American vernacular, raised a linguistic firestorm two decades ago.

In 1996 the Oakland, California, school board claimed that Ebonics, the dialect spoken by its majority population of African-American students, was a different language than standardized English, and they would take that into consideration when teaching their students. This sparked debate among writers and journalists, many who criticized the move.

Columnist Theresa Wilson wrote in the Iowa State Daily in 1997, “My heart tells me that Ebonics is not a language. Ebonics is not black English. It is bad English.”

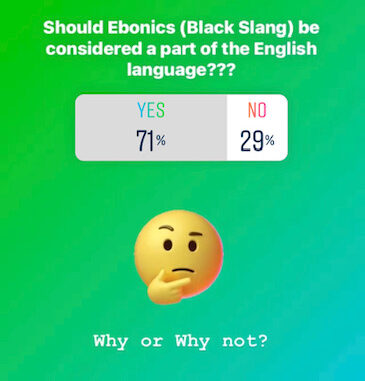

Even now Instagram users responding to an informal poll were divided. Among the 70 users who responded, more than 70% agreed that Black language belongs in the dictionary, but that left 29% who disagreed.

“Ebonics isn’t actually English. It’s a ethnic-cultural thing,” Diamond White wrote. “I would consider Ebonics more of a dialect than actual English language.”

White suggested that adding Black words to Dictionary.com was an attempt to be “woke,” crediting “White-guilt. I think it is Dictionary.com trying to be more inclusive to the Black community. I think it is them trying too hard.”

Some of the poll respondents suggested a separate dictionary.

“Mark Twain showcased Southern diction in his famous novels ‘Huckleberry Finn’ and ‘Tom Sawyer,’ really showing the evolution of the English language,” wrote Ashlyn Benson. “I think Ebonics should hold as much validity as the novels they were showcased in. However, I don’t think Ebonics should be featured in a standardized dictionary unless it was a dictionary that only featured Ebonic words.”

Such dictionaries do exist. A staple in Black culture has included the popularization of Urban Dictionary, a website that allows for users to share popular slang words with their personalized definitions.

Many who agreed with recognizing Black language suggested that those who disagree are anti-Black.

“People undervalue Black people all over the world, even when they are the creators of great things,” Robyn Lewis said. “They probably said the same thing about the traffic light before they found value in it.”

Kelly of Dictionary.com, agrees that having Black language in the dictionary solidifies its validity and value.

“The words that are in the dictionary have effects on real people,” Kelly said. “When a group sees the language they use represented in the dictionary, it’s validated. It shows that their language is real and it matters.”

It’s not just a matter of validating language that exists, according to Zaniah Shobe, who wrote a widely regarded paper on Black language while an undergraduate at the University of Louisville.

Her paper was protesting the idea that speaking “Black” equates to speaking poorly.

“When I talk Black,” she wrote, she felt as if those around her reacted as if “I clearly do not understand where I am at and somebody needs to tell me to talk right if I want the job, scholarship, even the respect I deserve. Being a human is not enough and especially not being a black person will I get the respect I deserve unless I sound white.”

Shobe, reached in August, recalled that in the freshman English class in which she wrote the paper, “my teacher didn’t mind if we spoke with Ebonics. I wanted to highlight that if one person can accept it, why can’t everyone else?”

She says that part of the reason for choosing her topic was to signify a need for change in the way Ebonics is viewed. “The Black community plays a huge part in everyday life, so why can’t we (and our language) be fully accepted?”

Be the first to comment